James Shyr and team show and tell us what’s on the horizon…

James Shyr knows a few things about building car design teams in China. When General Motors dispatched him from Detroit in 2001 to establish a design studio at the Pan Asia Technical Automotive Center (PATAC), a SAIC-GM joint-venture engineering facility in Pudong, he was the only designer among 20 staff – and for a short while, the only GM design staff across East Asia.

As design director over the next six years, Shyr helped oversee PATAC’s expansion from localising models for the domestic market to developing complete models sold in Greater China, Asia and beyond, including Buick, Chevrolet and Cadillac models as well as local brand Baojun.

Today, Shyr is once again spearheading an automotive design studio, this time for Human Horizons, the electric vehicle and mobility tech startup that he joined last year as chief design officer. But things have changed since Shyr last started a studio in Shanghai. The automotive and design landscape is as developed and crowded as the jutting skyline that has risen in Pudong. Human Horizons is among hundreds of electric vehicle startups in China, the company’s design centre merely another of dozens that have recently opened or expanded, with competition for resource ever fiercer.

But Shyr, who has worked considerably in the US and Taiwan, still sees China as a land of opportunities, especially in EV and smart mobility. “I have seen China’s auto and design industry go from nothing to something and reach a world-class level. It is still like Detroit was in the 1930s – anything can and will happen,” he says.

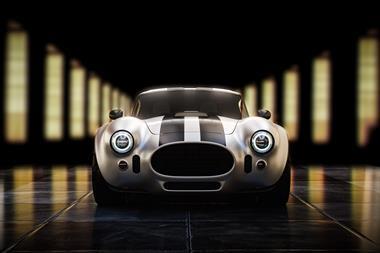

The studio, located in the Yangpu district north of the Bund, already has momentum. Last autumn, the company debuted a demonstrator with four wheel-hub motors along with two concepts, the three-seater Concept H and urban pod Concept A, which both established the carmaker’s self-described ‘human-oriented’ design strategy, along with strong aerospace overtones. Last week (2nd April), its Concept U revealed similar features, but with a more spacious interior.

This summer it will reveal a new ‘brand X’ and production preview model, which the company plans to build at the end of 2020 at a yet-to-be-determined factory north of Shanghai in Yancheng municipality (which is also a principal investor in Human Horizons).

Unlike GM or other established OEMs at which many Human Horizons executives worked previously, the startup is an opportunity to shape a brand without legacy. Shyr says the design studio in particular will influence not only the vehicles but how the company develops its other ‘smart’ business divisions, and even manufacturing.

“We are completely co-developing the brand from a design perspective, and then we are trying to build the factory from that,” Shyr says.

Mark Stanton, the company’s chief technical officer, also revels in the opportunity to design and engineer vehicles without existing hardware and assets. He worked more than 40 years with Ford and later Jaguar Land Rover, including a key engineering role on the Jaguar I-Pace electric vehicle, which broke many moulds for the brand in design and UX. “But that was almost an exception,” he admits. “As a non-traditional OEM, we want to take risks and we have taken risks together with our engineers and designers.”

This attitude is evident from Human Horizons’ initial concepts and studio sketches, which established a design language that conjures up sci-fi and aviation design. The panoramic glasshouse of the Concept H, for example, uses an electrified polymer that dims or brightens the glass, as used on the Boeing Dreamliner. There is a space-age, zero-gravity character to the concepts’ sleek shapes, panoramic windscreens and shaded tints – “a bit of dark flair”, as design senior director Riaz Sherazee describes them.

At the same time, human elements emerge, whether in its muscular form, immersive HMI or cultural considerations. The 2+1 seat Concept H (for Hypervelocity) uses drive-by-wire technology that allows the steering wheel to move to any seat, using VR in the rear seat to create a new type of backseat driver. “This the ‘king seat’, and relates to the fact that in Chinese culture, the boss likes to sit in the back,” says Sherazee.

The vehicle’s packaging uses the hub motors to create a complete airflow front-to-back on both sides of the car. “Imagine putting a sieve through water, which cuts through more easily than a plate,” says Sherazee. “That is why we went with a three-seater configuration to enable the airflow through the car without going through the passenger. It’s an example of designing the car from the inside out.”

Shyr and Sherazee reveal that the production model will be premium and difficult to categorise, aimed at young ‘post-millennials’. It won’t include the hub motors or airflow channels, however at the insistence of the company’s chairman, Ding Lei (a former general manager at SAIC-GM), the technology and materials that designers use in concepts must not be ‘laughable’, says Sherazee, but indicate future use.

Its latest Concept U hints towards a continuation of key features, such the panoramic windscreen, striking lighting signature at the rear, flat floor and large aero channels. It also has front and rear wheel covers similar to the rear versions on the Concept A city pod, which featured a subtle cut line from which different bodies could be swapped.

Human Horizons’ studio currently has around 20 in-house designers and works with another 20 in contracted services. James Shyr expects staff to grow to around 60 designers by the end of this year, and 90 by the end of 2020.

The studio is compact but spread over two floors with designers working mainly on digital sketch, rendering and data tools. The team is largely Chinese, but led by international veterans, including Sherazee, who worked with Shyr at PATAC in 2003-2006, and was later lead designer at Ford.

To Mark Stanton’s admitted disappointment, Design is housed separately from Engineering, which is in a new technology campus nearby. However, the company has acquired land for an expanded R&D centre that will bring them together. The initial plans are for a new studio with full design capabilities, including 6000 sq.m for up to 120 people, 50 metres of service bays, VR rooms, 3D printing and a five-axis milling machine for modelling. Although the plans are not fully confirmed, a vehicle viewing platform is planned for on top of the building.

The company also intends to open overseas design studios, initially in California and Germany, as well as an industrial design centre in Barcelona.

The studio is also set to play a role in the company’s other business ventures. Human Horizon’s vague but ambitious ‘3-Smart’, ‘H-U-A’ strategy will be geared towards technology that’s focused on electronic architecture and alternative powertrains for vehicles (H), ‘V2X’ vehicle-to-road communication for smart transport (U) and shared mobility and connectivity for smart cities (A). The vehicle will be central, both as a data point, but also in its design philosophy.

“The way we design our vehicles is going to be central to our overall 3-Smart ecosystem,” says Stanton.

James Shyr admits that recruiting staff is nevertheless a challenge in China, and that the company’s vision can be off-putting to designers more interested in traditional disciplines. In fact, sometimes the youngest, least experienced designers are most reluctant. (See our story on this last year.)

“We have taken in quite a few experienced people who are more willing to take risks than younger designers, especially those who may still want to learn some basic skills and get their careers started,” he says.

Nevertheless, the company is an opportunity for designers interested in how technology can not only reshape a vehicle, but also wider transport and urban infrastructure in the future.

“With our designs, we want to reflect the technology innovation, which is why one of our core values is ‘sci-fi’,” says Sherazee. “We are not just doing another beautiful car, but we want to reflect this new-age innovation and interaction across all that we do.”